Van I2959 naar LAP: Mijn reis naar het upgraden van hydrogel fotocureertechnologie

Hi, I’m Starry. I’ve been working with photocurable materials in the lab for over a decade. If you’re struggling with uneven hydrogel curing or unsatisfactory cell viability in bioprinting, or if you’re frustrated with the common problems of traditional photoinitiator I2959, then you’ve come to the right place. Today, I’ll share my experiences, both successes and failures, and discuss in detail the “star” photoinitiator, LAP, so you can not only understand why it’s so good but also learn how to use it effectively.

I. Why is LAP considered a “game-changer” for biomedical hydrogels?

I remember seven or eight years ago, our lab exclusively used I2959. It was a reliable “old workhorse,” but as our cell encapsulation experiments became more sophisticated, problems arose: slow dissolution, the need for UV curing, and insufficient biocompatibility. It wasn’t until LAP came into my view that the entire workflow truly became smooth.

LAP’s core advantages go far beyond simply “good water solubility.”

Its greatest innovation lies in perfectly combining efficient photoinitiation with excellent biocompatibility within the cell-friendly blue light window of 405 nm. This is like equipping delicate surgical procedures with a sharper, safer scalpel. I conducted comparative experiments: in the same GelMA prepolymer solution, 0.1% (w/v) LAP cured nearly twice as fast under a 405 nm light source compared to the same concentration of I2959 under 365 nm, and the curing depth and uniformity were visibly improved. This directly means that we can better maintain structural fidelity when constructing tissue engineering scaffolds.

II. Delving into the Molecular Level: Deconstructing the “Efficiency” and “Safety” of LAP

Many product manuals only tell you the results, but as frontline researchers, we must understand the “why” behind them. This can help you avoid many application pitfalls.

1. Lithium Phosphate Salt Structure: The Dual Code of Water Solubility and Cell Compatibility

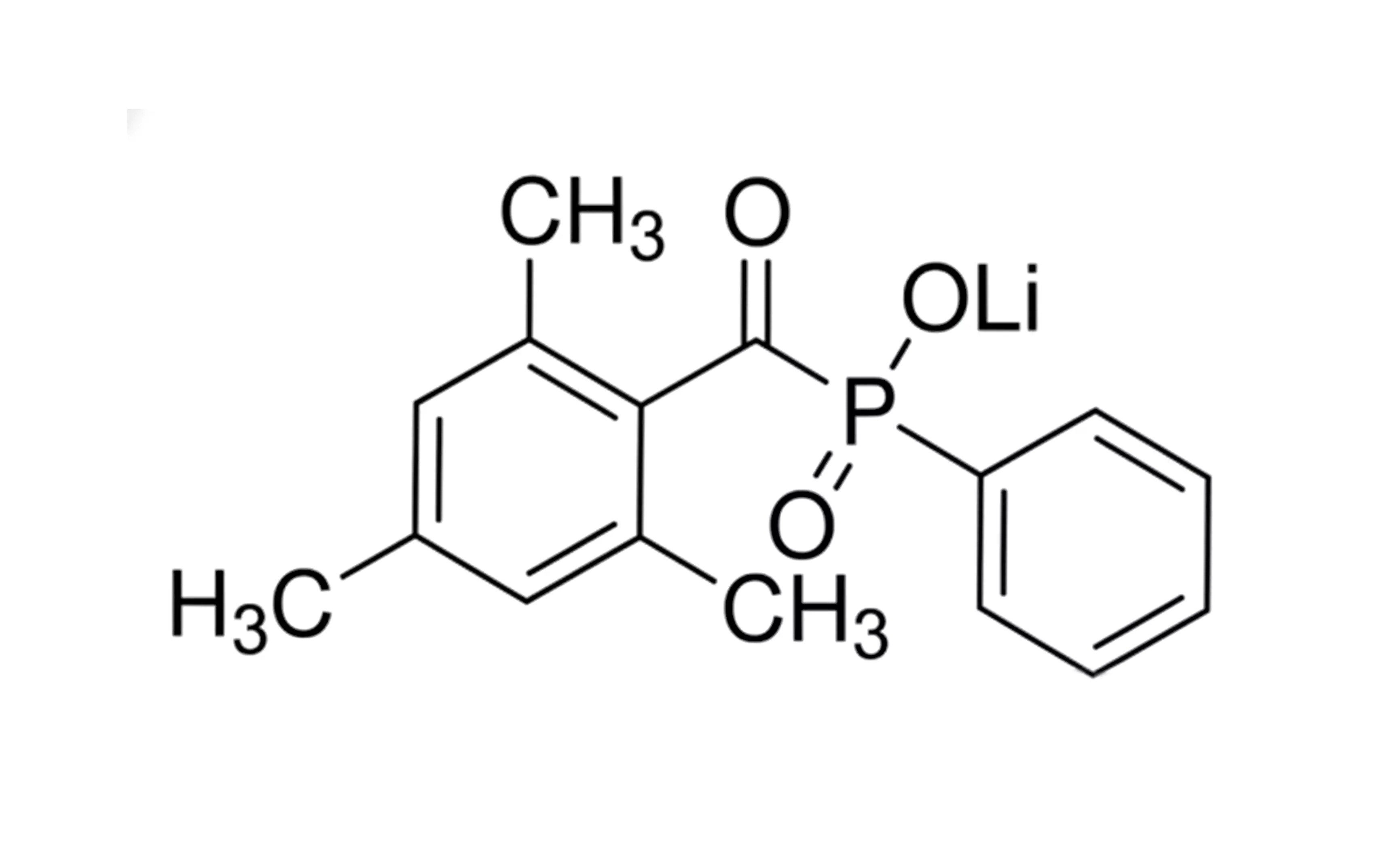

The full chemical name of LAP is “phenyl(2,4,6-trimethylbenzoyl)lithium phosphate.” This “lithium salt” structure is key. It gives LAP astonishing water solubility—reaching approximately 47 mg/mL in pure water, which is nearly dozens of times higher than I2959. High solubility leads to a homogeneous solution state, which is the physical basis for uniform crosslinking.

LAP photoinitiator

More importantly, its photolysis products are relatively simpler and less acidic. I have monitored the pH changes of the culture medium during long-term cell culture experiments. Gels cured with LAP maintained a more stable environmental pH than systems using I2959, which is crucial for tissue culture that needs to be maintained for several weeks.

2. 405 nm Blue Light Excitation: A Leap from “Tolerable” to “Friendly”

The maximum absorption wavelength of LAP is around 384 nm, perfectly matching the 405 nm blue light LED. This is a strategic advantage. It is a consensus that ultraviolet light (especially below 365 nm) poses a risk of DNA damage. 405 nm blue light, however, is significantly safer. In our team’s experiments encapsulating mesenchymal stem cells, we found that the 24-hour cell survival rate in the group using 405 nm curing was 15%-20% higher on average than the group using 365 nm UV curing.

My Practical Checklist: Light Source Selection and Parameter Optimization

- Preferred light source:

High-intensity 405 nm LED point light source or mask lithography machine. LED light sources generate less heat and have stable light intensity.

- Light intensity is key:

Stronger is not always better. Typically, a light intensity range of 5-20 mW/cm² is the “sweet spot” for balancing curing speed and cell safety. It is recommended to perform a light intensity gradient experiment first.

- Exposure time:

Adjust in conjunction with light intensity. For LAP concentrations of 0.1%-0.25%, start with exposure times from 10 to 60 seconds.

III. Laboratory Practical Guide: How to Effectively Use LAP?

Even the best theory needs practical application. Below are the steps and suggestions I’ve summarized to help you avoid common pitfalls.

1. Preparation and Storage: Details Determine Success

LAP is a powder, and while stable, it is sensitive to moisture and light. My practice is as follows:

- Stock Solution Preparation:

Use a light-blocking brown bottle to prepare a 10-20 mL 1% (w/v) stock solution (e.g., 100 mg LAP dissolved in 10 mL PBS or deionized water). Sterilize by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter, aliquot into small portions (e.g., 1 mL/tube), and store at -20°C in the dark. This will last for a month, avoiding repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Working Concentration:

For most cell encapsulation applications, 0.05%-0.25% is a safe and effective starting range. For cell-free hydrogel solidification, lower concentrations can be tried.

2. Fine-Tuning for Specific Applications

- High-Precision Biological 3D Printing:

If your bio-ink has high viscosity and slow printing speed, it is recommended to use the upper end of the concentration range (e.g., 0.2%-0.25%) to ensure that the extruded fibers solidify quickly after extrusion, guaranteeing structural accuracy.

- Direct Cell Encapsulation:

To maximize cell compatibility, use the lower end of the concentration range (e.g., 0.05%-0.1%) and combine it with appropriately longer exposure times but moderate light intensity. “Low concentration, long exposure” is often gentler on cells than “high concentration, short exposure.”

- A question I am often asked:

“Can LAP be excited with UV light (365 nm)?”

The answer is: Yes, but the efficiency is not optimal. LAP also absorbs at 365 nm, but its molar extinction coefficient is lower than its characteristic peak at 384 nm. This means you may need to slightly increase the concentration or exposure time. Therefore, unless limited by equipment, please stick to a 405 nm light source.

III. Laboratory Practical Guide: How to Effectively Use LAP?

Even the best theory needs practical application. Below are the steps and suggestions I’ve summarized to help you avoid common pitfalls.

1. Preparation and Storage: Details Determine Success

LAP is a powder, and while stable, it is sensitive to moisture and light. My practice is as follows:

- Stock Solution Preparation:

Use a light-blocking brown bottle to prepare a 10-20 mL 1% (w/v) stock solution (e.g., 100 mg LAP dissolved in 10 mL PBS or deionized water). Sterilize by filtration through a 0.22 μm filter, aliquot into small portions (e.g., 1 mL/tube), and store at -20°C in the dark. This will last for a month, avoiding repeated freeze-thaw cycles.

- Working Concentration:

For most cell encapsulation applications, 0.05%-0.25% is a safe and effective starting range. For cell-free hydrogel solidification, lower concentrations can be tried.

2. Fine-Tuning for Specific Applications

- High-Precision Biological 3D Printing:

If your bio-ink has high viscosity and slow printing speed, it is recommended to use the upper end of the concentration range (e.g., 0.2%-0.25%) to ensure that the extruded fibers solidify quickly after extrusion, guaranteeing structural accuracy.

- Direct Cell Encapsulation:

To maximize cell compatibility, use the lower end of the concentration range (e.g., 0.05%-0.1%) and combine it with appropriately longer exposure times but moderate light intensity. “Low concentration, long exposure” is often gentler on cells than “high concentration, short exposure.”

- A question I am often asked:

“Can LAP be excited with UV light (365 nm)?”

The answer is: Yes, but the efficiency is not optimal. LAP also absorbs at 365 nm, but the molar extinction coefficient is lower than its characteristic peak at 384 nm. This means you may need to slightly increase the concentration or exposure time. Therefore, unless limited by equipment, please stick to a 405 nm light source.

IV. Looking Ahead: After LAP, where is the next breakthrough point?

LAP has significantly advanced the field of biomanufacturing. However, based on discussions with my colleagues, the next frontier may be “dynamic photocuring.”

Currently, we use one-time, irreversible curing. But in the future, will it be possible to develop photoinitiator systems that respond to specific wavelengths (such as far-red light or two-photon excitation), and whose curing degree or mechanical properties can be “adjusted on demand” or “locally erased”? Imagine printing a cardiac patch and then being able to remotely and gradually adjust its hardening process using non-invasive deep-tissue light to better match the growth rhythm of the native tissue. This might require entirely new molecular designs, such as coupling LAP’s photosensitive groups with reversible reaction

Finally, I’d like to pose this question to you: What are the biggest challenges you’ve encountered when using LAP in your specific research or application? Is it controlling the mechanical properties of the solidified gel, or achieving long-term stability in co-culture with specific cell types? Please share your experiences; let’s discuss this together.